-Archigram:

Group of English designers formed by Peter Cook, Ron Herron, Warren Chalk

(1927–88), and others in 1960, influenced by Cedric Price (especially his Fun

Palace of 1961), and disbanded in 1975. Archigram provided the precedents for

the so-called High Tech style, and promoted its architectural ideas through

seductive futuristic graphics by means of exhibitions and the magazine

Archigram: buildings designed by the group resembled machines or machine-parts,

and structures exhibited their services and structural elements picked out in

strong colours. The group's vision of disposable, flexible, easily extended

constructions was influential, although very few of its projects were realized

(the capsule at Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan, was one). Richard Rogers's

architecture derives from Archigram ideas, while Price's notions of

expendability influenced Japanese Metabolism. Unrealized but influential

projects include the Fulham Study (1963), Plug-in City (1964), Instant City

(1968), the Inflatable Suit-Home (1968), and Urban Mark (1972). Herron's

Imagination Building, London (1989), encapsulated something of Archigram's

ethos.

| > | |

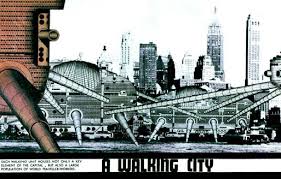

Walking City in New York, 1964

Ron Herron, Archigram Courtesy Ron Herron Archive | ||

-Japanese

Metabolist: In the 1960s a group of Japanese architects dreamed of future

cities and produced exciting new ideas. The visions of Kurokawa Kisho, Kikutake

Kiyonori, Maki Fumihiko, and other architects who had come under the influence

of Tange Kenzo gave birth to an architectural movement that was called

"Metabolism." The name, taken from the biological concept, came from

an image of architecture and cities that shared the ability of living organisms

to keep growing, reproducing, and transforming in response to their

environments. Their ideas were magnificent and surprising, with concepts such

as marine cities that spanned Tokyo Bay, and cities connected by highways in

the sky where automobiles pass between clusters of high-rise buildings.

Metabolism

emerged at a time when Japan had recovered from the devastation of war and

entered a period of rapid economic growth. People felt that creating ideal

cities would be a way to build better communities. This exhibition is the very

first to make a comprehensive examination of Metabolism. Japan is now facing

big decisions about its future. It is a perfect time to learn about the

Metabolism movement and discover some of its many hints for architecture and

cities.

The

exhibition is organized in four sections, plus the Metabolism Lounge.

Kurokawa Kisho,1970

-Cedric Price: CEDRIC PRICE (1934-2003) was one of the most visionary architects of the late 20th century. Although he built very little, his lateral approach to architecture and to time-based urban interventions, has ensured that his work has an enduring influence on contemporary architects and artists, from Richard Rogers and Rem Koolhaas, to Rachel Whiteread. Price – or CP, as he was called – was born at Stone in Staffordshire in 1934 to an architect father, AJ Price, who worked for the firm which built the Odeon cinema chain.

In the early

1960s the UK experienced the onset of the first consumer society modelled after

the US in which automation and communication technologies placed the individual

in a new relationship to the community. The works of young architect Cedric

Price reflect the emergence of the mass market and mass media, and demonstrate

the influence of a technologically orientated architecture on the idea of

social networks.

Based on

central projects the dissertation processes the ideas and concepts of Cedric

Price in the period 1960 to approx. 1980, to demonstrate the change from an

object- to a process-oriented architecture concept, which prompted a rethinking

in the planning and design methods of architecture: from an object-based

approach to architecture to the concept of a demand-driven environment.

Assuming the

technological approach taken by Cedric Price in his projects, the work examines

the influence of system thinking and social organisation on the start of a

sustained concept of architecture and demonstrates how the influence of

information technologies, automation and the science of cybernetics in

architecture produced new concepts of spatial organisation. Cedric Price saw

the city and its architecture as part of a total system in which social,

political and economic processes created a culture of permanent exchange. The

idea of exchange and interaction divert the focus of architecture to the

organisation of participative, open-ended processes.

Cedric Price, Fun Palace, axonometric section, circa 1964. Cedric Price Archives, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal.

-Haus- Rucker: in the late 1960's and early 1970's, haus rucker co, along with archigramand superstudio, propelled architecture towards a different kind of future. sharing their own aesthetics with the aesthetics of space travel, comic books, sci-fi, barbarella, dada, fluxus, and whole mess of other pop culture references; these groups changed the conceptual architectural landscape forever.

haus rucker

co was formed by laurids ortner, günther zamp kelp and klaus pinter in vienna,

in 1967. for 10 years, under the haus rucker co moniker, they produced

prototypes, drawings, and forms for numerous major exhibitions such as

documenta 5 in 1972. these pictures are from a super rare catalog of their show

at the museum of contemporary crafts in 1969 in new york (yes, i just about

fell over when i found it in a used book store in ny several years ago!). the

design of the catalog is obviously meant to mirror an LP cover - and

specifically a LIVE LP. the intention is clear - we are not stuffy academic

architects; we are going to shape the future. although they made extensive

spatial explorations with inflatable forms, i think their concerns were not

solely architectural, but an attempt to expand and explore social interaction

both inside and outside of designed spaces. many of their projects, such as the

1967 mind expander, were for two people to experience together; and the choice

of invisibility of structure towards complete visibility of inhabitants is

certainly pointed.

The booklet

documents, amongst other things, their pneumacosm project, which was a

predecessor of their oasis 7 for documenta. the proposal for ny was to create a

multitude of clear pneumatic "dwelling units" on the outside of

existing buildings in the downtown nyc landscape. i think that along with the

notion of adding space to finite structures is the idea of people living in

clear view of each other - keeping the inside inside, but also bringing the

inside outside, and changing the way we define both terms... one more beautiful

60's utopian dream...

In 1972, the Austrian architecture collective Haus-Rucker installed Oasis Nr 7 at Documenta 5.

In 1972, the Austrian architecture collective Haus-Rucker installed Oasis Nr 7 at Documenta 5.

-Coop

Himmelblau: is a cooperative architectural design firm primarily located in

Vienna, Austria and which now also maintains offices in Los Angeles, United

States and Guadalajara, Mexico. In German, "coop" has a similar

meaning to the English "co-op." "Himmel" means sky or

heaven in German, and "blau" means "blue" while "bau"

means "building." So, the name can be interpreted as "Blue

Heaven Cooperative" or "Sky Building Cooperative"

Coop

Himmelblau was founded by Wolf Prix, Helmut Swiczinsky and Michael Holzer and

gained international acclaim alongside Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry

with the 1988 exhibition, "Deconstructivist Architecture" at the

Museum of Modern Art. Their work ranges from commercial buildings to

residential projects.

BMW Headquarters, Munich, Germany

BMW Headquarters, Munich, Germany

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder